Since the opposition ousting of Bashar al-Assad in Syria, Western powers have cautiously embraced Interim President Ahmad al-Sharaa as the country’s new legitimate leader. The new Syrian government, consisting of technocrats and high-profile former dissidents of the Assad regime, is actively reaching out to international actors in a quest to rebuild bridges.

The Syrian president’s diplomatic visits to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Qatar, Jordan, France, and Turkey seemed auspicious and held promising potential. However, his potential in-person attendance at the Arab Summit in person was the center of some controversy.

Baghdad’s position on the rapid developments in Syria is split between two camps: The official government and that of the powerful non-state actors.

The Iraqi government’s initial response to Syria was cautious, including the closure of border crossings and the deployment of troops to the 630-kilometer border with Syria. But Baghdad slowly shifted towards a more pragmatic approach and eventually sent its officials on formal visits to Syria, in a move that acknowledged the legitimacy of the new regime. These efforts culminated with the Iraqi prime minister’s April meeting with al-Sharaa in Doha, where he extended a formal invitation to the Arab Summit, which Baghdad hosted in mid-May.

Alternatively, Iran-affiliates in Iraq have vocally opposed such normalization efforts. Over fifty members of the Iraqi parliament, many of whom have close ties to the Shiite Coordination Framework, signed a petition to reject al-Sharaa’s Baghdad visit, and parliament member Mustafa Sanad even organized a protest against his presence at the summit. Additionally, militia leaders such as Qais al-Khazaali and Abu Ali al-Askari, who command militia groups that were active in Syria until recently, posted direct threats on their X accounts towards the Syrian president. Media platforms with Iranian affiliations have been working in parallel with politicians to promote a disinformation campaign about al-Sharaa’s criminal record in Iraq, by issuing fake documents and tampered proof of incarceration.

Iraqi militias have a long history of hostility towards some of the Sunni militant groups with which al-Sharaa was involved in previous years. These Islamist Jihadist groups rose to power in Iraq in 2014 and took over one third of Iraqi territories, subsequently the liberation of these areas was a lengthy and costly process for the Iraqis. Iraqi militias continue to use the same justification for their military intervention in Syria in the past years, which is the need to “protect” holy Shiite sites, and continue to insist that it remains a pressing issue even under the new regime.

Quiet hostilities and alliance of necessity

Under Baathist control, Syria had longstanding grievances with Iraq. Before the spark of turmoil in Syria, for example, Iraq’s former prime minister Nouri al-Maliki had accused Assad of sending militants and terrorists into the country. But economic ties, in part due to the movement of 1.2 million Iraqi refugees into Syria during the early aughts, softened hostilities. During this period, economic trade between Syria and Iraq reached its peak at four billion US dollars annually. At the time, 60 percent of Iraq’s imports came from Syria.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

But this dynamic shifted drastically after 2011 with the eruption of the Arab Spring and the anti-Assad uprising in Syria. Iran seized the opportunity to broker a new relationship between the two countries, where political and security interests were tied and emphasized, and sectarian fault lines were deliberately exploited. Iraqi militias, along with Iranian forces and the Assad regime, took part in suppressing the rebels’ seizure of Syrian cities during these years. Over fifteen Iraqi militias, with just over 75,000 fighters, were estimated to have participated in battles in Syria over thirteen years. In parallel, Iraqi territories provided a safe land corridor for Iranian reinforcement and personnel traveling to Syria, and three domestic drug trafficking corridors from Syria and Iran to neighboring countries.

Economic relations endured despite the security shakeup. Even after 2011, Iraq continued to import agricultural products from Syria in addition to food, textiles, plastic goods, medicine, and many other commodities. Syrian products comprised 80 percent of Iraqi markets; however, this percentage declined to only 5 percent after December 2024.

The new reality and future prospects

Iraq underutilized its agricultural capacity for years and depended on Syria for food security. By solidifying economic relations with the new Syria through trade agreements, transportation infrastructure, and meaningful investments, Iraq can further multiply the fruits of cooperation and guarantee water, food, and fuel security.

Since the historic overthrow of the Assad regime in Syria, Baghdad has sent three delegations with high-profile officials to meet with officials from the new government in Damascus.

The latest, in April, held the highest significance and marked the new Iraqi pragmatist approach to the recent developments with its neighbor. It included more specialized Iraqi officials like the head of the Iraqi National Intelligence Service, along with representatives from the Department of Border Enforcement, the Ministry of Trade, and the Ministry of Oil.

This delegation directly addressed economic interests in Syria, most notably the Kirkuk-Baniyas oil pipeline. Iraq currently exports oil through Basra Sea ports, land, and the Kirkuk-Ceyhan pipeline. However, resuming operations on a direct pipeline to the Mediterranean would result in substantial economic gains, increasing Iraq’s oil export capacity by 300,000 Bpd. Negotiating access for Iraq to the Syrian Mediterranean ports will diversify Iraq’s options in trade and the global supply chain. It will also decrease the costs of importing European goods and commodities to Iraq and other parts of the region.

Meanwhile, as the West slowly opens up to the new Syrian government, Iraq should also take part in the country’s efforts to rebuild as an influential neighbor. Iraq’s energy sector, in particular, is an institutionalized and mature one, and Iraq’s national oil companies can offer their investments in Syria’s natural resources. Iran’s power decline in the region not only left a political vacuum but also an economic one, too. And as Tehran’s expenditures in Syria ranged from thirty billion US dollars to above fifty billion dollars, and Iranian investments worth hundreds of millions of dollars were under construction at the time of regime change.

Additionally, Iraq hosts between 800 thousand to a million foreign workers, many of whom transfer their earnings in dollars back to their home countries— mostly southeast Asia—draining eight billion US dollars of foreign currency. Baghdad now has a golden opportunity to strengthen both its economy and regional ties by facilitating the legal entry and employment of Syrian workers into the private sector. As a source of affordable and skilled labor, Syrian workers can help meet domestic labor demands in the private sector, while their earnings, reinvested into the Syrian economy, can further deepen economic interdependence between the two countries.

The security question

However, stability must come first before economic prosperity.

While the international discourse is focused on minority rights and power-sharing guarantees, Iraq and Syria have a deeper understanding of the security challenges that are unique to them. The Iraqi-Syrian border witnessed the rise and fall of extremist groups that were behind some of the deadliest conflicts for civilians in recent years. The Iraqi government failed for years to secure the porous border with Syria and control illicit economic activities that thrived on the vulnerable periphery. Furthermore, the northern parts of both countries have suffered spillover effects of conflict between their neighbor, Turkey, and Kurdish rebel groups.

After the global coalition against the Islamic State (ISIS) successfully defeated the militant group, al-Hol prison and similar camps isolated ISIS families and the remnants from their surrounding populations. This ended up dragging many innocent civilians into these enclosures, including three thousand missing Yazidi women and girls who are believed to be entrapped in this camp and whose situation remains a pressing issue. Moreover, two thousand Assadist soldiers fled to Iraq in the first few hours of the regime’s fall, and were later returned to Syria by the Iraqi authorities.

Such incidents are likely to continue in Syria’s transitional period and can only be combated through cooperation with Iraq. Lastly, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s explicit comments about dividing Syria into four administrations to establish a so-called ‘David’s Corridor’ pose a direct threat to Iraq’s border integrity and internal security. Iraq—among other regional actors—must establish a joint approach to refute this hollow and short-sighted political agenda. A fragmented Syria risks becoming a persistent epicenter of regional instability.

Policy recommendations for the Iraqi government

At this turning point in the region’s history, Iraq has a rare opportunity to start a new chapter with Syria.

Welcoming the Syrian president in Baghdad to the Arab Summit could have served as the first practical step towards a new relationship, but this was not achieved due to continuous militia intimidation. The threats made by non-state actors resulted in the withdrawals and cancellations of many heads of state from the summit, including al-Sharaa, and instead sent low-level delegations. The Iraqi government should implement mechanisms to regulate and hold accountable militias and other non-state actors whose public positions contradict official state policy and risk undermining Iraq’s diplomatic relations.

Opening effective channels of communication between the Iraqi and Syrian governments will be critical in efforts to stabilize and normalize. The Iraqi government should continue with regular, high-profile official visits to Syria. This will ensure Iraq’s input in critical and strategic decisions faced by the Syrian government and guarantee a seat at the transition table.

These communications should be inclusive beyond government officials and extend to civil society, local communities, and tribal or religious leaders. In the midst of the current storm of misinformation and disinformation around the situation in Syria, granular relationships will help local communities adapt and respond to rapid transitions, especially with population movement and voluntary return of refugees.

To truly deepen a partnership between the two countries, Iraq should also work closely with the new Syrian regime to establish a high-level security cooperation, including immediate investments in border crossings and towns, to prevent the resurgence of extremist groups and smuggling activities across the joint border. These areas were neglected and under non-state actors’ control for years, and government takeover will mean a regulated, taxed, and monitored movement of goods and travelers.

And to enable prosperity after ensuring security, Baghdad should continue to identify economic opportunities and solidify them with memoranda of understanding, trade agreements, and investment deals. In the six months since the regime change in Syria, there has been a significant investment momentum and capital interest from regional and international actors. Therefore, supporting the Syrian-Iraqi business council has become a pressing necessity, as the efforts to rebuild Syria are mounting through direct foreign investments, as the Syrian economy recovers after lifting the sanctions. Feedback from businessmen on both sides will provide input on market gaps, demand potential, stakeholder engagement, industry trends, and trade dynamics. All of which can be used as a blueprint for economic cooperation.

Part of this picture should include Baghdad legalizing the status of Syrians who wish to stay in Iraq as part of the labor force. Iraq’s Ministry of Labor should create a legal framework to incentivize Syrian skilled workers’ employment in the Iraqi private sector. Doing so will curb the influx of undocumented and unregulated immigrant workers from outside the region, limit foreign currency outflow, and meet the private sector employment needs.

Over the past thirteen years, Iraq’s role in Syria has been marked by hardship and complexity. Now, the current Iraqi administration holds the opportunity to turn a new page and help shape a future defined by peace and regional cooperation.

Shermine Serbest is an Iraqi researcher and international relations analyst. She leads many data-focused projects covering Iraq, Iran, and the Middle East, focusing on misinformation and disinformation and the political economy.

Further reading

Wed, Mar 19, 2025

Why the United States must bridge the Iraq-Syria divide

MENASource By Sarkawt Shamsulddin

With leverage over both capitals, the United States emerges as the linchpin in delicate diplomatic moment between Baghdad and Damascus.

Wed, May 28, 2025

Sectarianism, social media, and Syria’s information blackhole

MENASource By

Since Assad’s December ousting, Syrians have struggled to sift the truth from fake claims about security incidents across the country.

Thu, Apr 3, 2025

Washington halted the Iraq-Iran electricity waiver. Here is how it’s perceived by Washington and Baghdad.

MENASource By Ahmed Tabaqchali, C. Anthony Pfaff

By making Iranian energy more costly, the United States hopes to incentivize Iraq to diversify its energy sources and reduce its dependency on Iran.

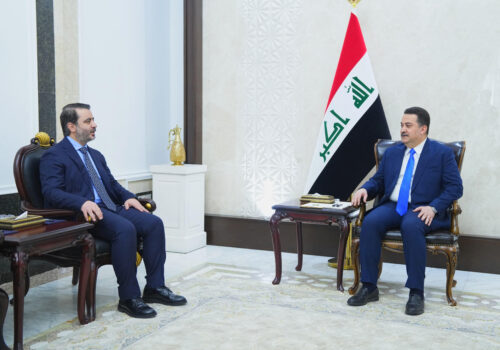

Image: Iraqi Deputy Foreign Minister Mohammed Bahrululum meets with Syrian Foreign Minister Assad Hassan al-Shibani ahead of the 34th Arab League summit, in Baghdad, Iraq on May 16, 2025. Murtadha AL-Sudani/Pool via REUTERS